Reflections on the “get.”

When tragedy strikes and lives are lost, people have many ways of expression, depending on the circumstances. Grieving and sometimes agonizing mental pain, remorse, and regret for a parent, partner, or God forbid: a child who passed away are part of what it means to be human. Anguish for someone you know or have known– just in passing– or for an outstanding coworker or community member, is part of who we are.

But what about a horrifying incident affecting someone you don’t really know, or a community in your own backyard? Of course, you’re going to empathize. And yes, you might turn to the news or social media to find out more or to opine. Perfectly normal. Yet think for a moment about someone whose job it is–and this is a job make no mistake about it– to encourage family members of a deceased person to talk to them for a news article or broadcast news report.

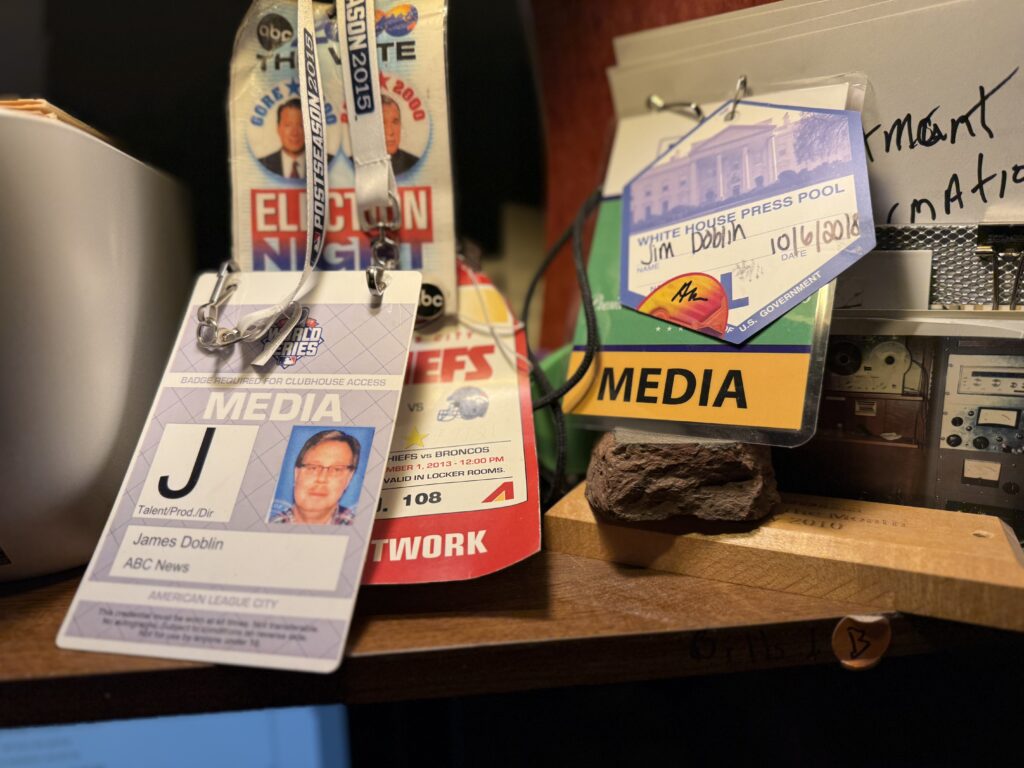

I’ve been such a person in my career. In network news, it’s politely called a “producer,” a term I can stand, or a “booker,” which I cannot. A booker is the person whose job is to get the family or close relatives of the tragedy to speak about their loss, the kind of individual their loved one was, and anything else about the situation on their minds This is referred to by the news business as “the get.” Sounds cruel and dehumanizing at the very least. And for me, the term engendered guilt. How in the hell can someone be so callous as to attempt an interview with those whose pain and loss is so sudden and horrific that you feel like a slimy, muckraking vulture? Sometimes this unenviable task means days of “camping out” at or near the family members, and walking over each other to get “the get.” It’s a sickening feeling oftentimes. It was my least favorite part of the career.

The most recent example of this is the death in Minneapolis of Renee Nicole Good. Feelings on this run the gamut in an even more polarized world. Just a few years ago, I had to be that horrible vulture at crime scenes, shuttle explosions, or murders such as the one that occurred in the Kansas City Chiefs parking lot.

Good’s relatives live in a town not far from me. And I know had I remained in the news business, I would have been summoned by someone in a cubicle in New York, to get the interview. I’m sure every producer-booker is in overdrive on this one. It is horrible to think about the circumstances and how this family must be in shock, grief, or maybe anger. Many a door was slammed in my face. Back in the 90’s, one network used to have the booker lay a flower arrangement or even worse–a fruit basket with his or her card and a short note at the family’s front door. “I can’t imagine the grief you are going through. But if you or a designated person wants to talk, I’m here”. That or some variation would be relayed to the persons of interest. Then the wait, sometimes the agonizing wait : days, maybe weeks. Remember, these are terrible times, and the booker sometimes–not all times– may be doing more harm than good. The key is to know how to say enough, and to back away. In that way, bookers/producers/whoever might be able to bring the story one step further with a great interview or pictures.

Skidmore, Missouri, comes to mind as I write. It was the horrible death of a woman whose fetus was ripped from her womb. Every network and news organization was there waiting to talk to the family and the bereaved father. Reporters were not welcome in Skidmore for a variety of reasons, including a violent attack on the town’s “bully” many years before. I spent about a month there. Never got the “get.” No one got it until the New York Post reportedly paid the family thousands of dollars for his story. Even now, reflecting on this makes my stomach churn. Reporters or any non-resident were often tailed and threatened with firearms. I recall standing in the middle of an intersection on a cold, cloudy morning looking for a cell signal, and an older man with a shotgun approaching me shouting, “Get the hell outta town!” We did eventually, even as the story “had legs.”

Sadly, it’s one of the worst things about being a journalist. But here’s the thing. It turns out many family members DO want to talk after a period of time. They want people to know their loved one; his or her legacy, his or her impact on this world. They want people to know, for whatever reason. The current political situation has only ratcheted up the booker’s task. It’s not a good time to be a professional journalist, let alone the sometimes slimy booker’s job. Make no mistake, this IS a job, and many times the results are a deeper understanding who this person WAS, or how the family plans to memorialize their relative. In the case of the man killed in Arrowhead Stadium’s parking lot, his relatives had nothing to say for quite some time. The night it happened, I had to knock on their door and briefly spoke to the victim’s father, who was a retired police officer. Sure, getting his widow and father to talk was a feather in my cap, but I never bothered them except to leave my card “in case.”

Our country has gotten more violent since my days as a booker (even hate to type this). There are many more real risks to a journalist or anybody, for that matter, who cares to express their opinion. I simply hope for compassion, polite discourse, and reflection on what’s truly important: a woman who mattered to her family and her community is no longer with us. And how can situations like this be handled more peacefully in the future.

I don’t envy any journalist who has to get “the get” today.